Roberto Batisti

Da Ginevra […] un bel giorno scompariva. Lo cercavano… e lo trovavano nei bassifondi di Marsiglia, mettiamo, che orgiava, si ubriacava. Aveva proprio questi brani di follia ciclica… come nella vita, così nell’attività scientifica.

G. Contini su F. De Saussure

Nell’era del punk rock, gli inviti al descensus ad inferos prendevano un significato particolarmente pregnante – quantomai concreto (gli scalini, appiccicosi di birra e ammantati di fumo, che conducono al club, e/o alla stazione del metrò, per raggiungere dagli angoli più remoti della metropoli i centri nevralgici della vita notturna) e insieme metaforico, non solo nel senso sociale e politico (degradarsi, ingaglioffarsi, entrare in clandestinità) ma anche esoterico: uscita dal mondo, morte sociale e rinascita a vita nuova. Ma sempre col rischio che la morte si facesse, da metafora, sinistra realtà.

Ascoltiamo lo strillo ispirato di Poly Styrene degli X-Ray Spex, in “Let’s Submerge”:

Come on kids don’t hesitate

We’re going down to the underground

We’re going down, we’re going down

To the underground

Con parole molto simili anche i Jam e i nostrani Gaznevada annunciavano di voler going underground; ma se nell’orgoglioso proclama di Paul Weller c’è soprattutto il ritiro da una società incomprensiva e incomprensibile, e forse nell’ipnotica cantilena del gruppo bolognese (che ce ne consegna due versioni in due anni, una cavernosa e una raggelata) è implicata con cupo compiacimento una discesa nel vizio o nell’illegalità, colpisce il risoluto entusiasmo nella voce di Poly Styrene. Sguaiato, ma quasi trascendente. Suona come una chiamata alle armi – ma di segno positivo, non negativo come nella ritirata sdegnosa, per quanto energica, di Weller. Non si tratta di secedere, ma di accedere, parrebbe, a una realtà segreta e nuova, d’infinito potenziale, e perciò adrenalinica. Lasciamoci prender per mano da questo insolito Virgilio.

Gli ipogei degl’inferi punk sono caratterizzati in senso decisamente infernale, con tanto di effettacci di lava e di zolfo:

The subterranean is a bottomless pit

The vinyl vultures are after it

Moulten lava, sulphur vapours

Smoulder on to obligerate us

In questo scenario neo(n)-dantesco s’incontrano però dei dèmoni molto particolari:

The Hades ladies, they’re dressed to kill

Dagger glares from Richard Hell

Tension heightening, heating, frightening

Thunder rolls as fast as lightning

Gli inferi della Londra punk sono carichi di tensione erotica; fra le provocanti dame infernali tirate a lucido e il primo animatore, massimo intellettuale e supremo Casanova della scena punk newyorkese volano sguardi come pugnali. Chi ha incrociato, anche solo su certe foto di copertina, gli occhi spiritati di Richard Hell può figurarsi facilmente il magnetismo davvero diabolico con cui il cantante dei Voidoids poteva stregare il pubblico – e le signore in particolare – anche durante quelle tournée britanniche che pure non gli lasciarono affatto una buona impressione.

E il nom de punk di Richard Meyers (che a lui, simbolista francese trapiantato nell’East Village, veniva da suggestioni rimbaldiane di Saison en enfer molto più che da satanismo dozzinale e subculturale) non è solo la traduzione dell’ellenico Hades, ma entrambi sono legati da profonde connessioni, anche etimologiche, al tema catabatico della canzone. Come gli eresiarchi della scena punk avevano visioni di orge luciferine e concerti come riti misterici sotto la crosta della metropoli post-industriale, così il filologo vede sotto i testi – anche quelli urlati e scapigliati del rock espressionista-esistenzialista che chiamiamo punk – formicolare la trama sommersa delle etimologie.

con occhiali leggeri sul naso appuntito, teneva il giaccone aperto su una maglietta attillata di taglio niente affatto militare, recante su due rotondità prorompenti la scritta Punk’s Not Dead. […] lei è Maggie Kimberly, filologa.

V. Evangelisti, La Sala dei Giganti

Se Ade è, probabilmente, l’Invisibile (ho A-widēs), il nome germanico dell’inferno (hell, Hölle, e in antico nordico Hel, la dea dei morti) deriva dalla radice indoeuropea *ḱel–, ‘nascondere’ del latino celare. E l’antico irlandese ha la perifrasi téit for cel – letteralmente ‘va all’occultamento’, e cioè – ‘muore’. Quanto al sommergere, una perifrasi di senso affine è contenuta, credo, nel greco kolymbân ‘tuffarsi’ – quindi ‘andar sotto copertura’ (going under-!).

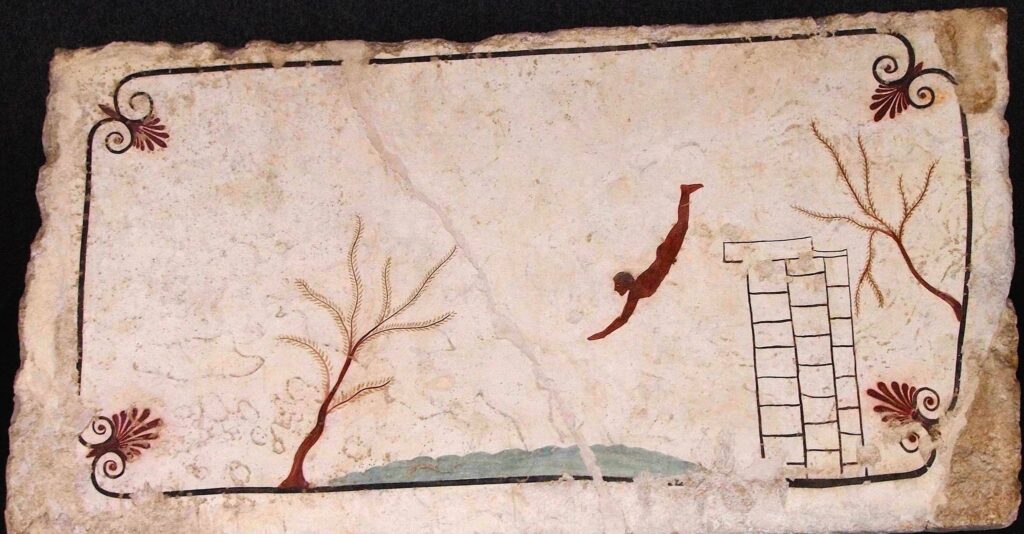

Il tuffo, d’altronde, è nella cultura greca immagine del trapasso fra questa vita e l’altra. Pensiamo alla celebre tomba del tuffatore di Paestum, insieme a tante altre testimonianze artistiche e letterarie: dalle perdute ‘Tuffatrici’ (Kolymbôsai) attribuite ad Alcmane, ad Anacreonte che minaccia il salto fatale: “dalla rupe di Leucade / nell’onda bianca mi tuffo (kolymbô) ebbro d’amore”. E per un personaggio del comico Ferecrate – che probabilmente parodiava i culti misterici – l’aldilà è qualcosa in cui ci si può tuffare (kolymbân) per raggiungere una sorta di paese di Cuccagna…

Ritroviamo *ḱel- probabilmente anche in kalýptō, ‘nascondere’, che fin dalla prima grecità letteraria può indicare proprio il nasconder/si sotto la superficie delle acque – tre volte, in ‘Omero’, la clausola allitterante kŷma kálypse “…l’onda nascose”… Un nome ‘parlante’ tratto da questo verbo è quello della ninfa Calipso, che nasconde Odisseo nella sua isola, con una sottrazione al mondo che è facile vedere come una morte figurata. E infatti studiosi come Hermann Güntert hanno voluto vedere in lei una remota discendente di antiche divinità indoeuropee della morte. Ma c’è anche un’altra Calipso, probabilmente distinta da questa, una delle figlie di Oceano: di cui non sappiamo se abbia mai aiutato un dio o un eroe a nascondersi nelle acque dell’aldilà, ma che forse, in quanto creatura acquatica, giocava semplicemente a tuffarsi nelle onde del mare.

Tutte queste risultanze quadrano col fatto, già ben noto, che in tutta la cultura degli antichi popoli indoeuropei (e non solo in quelli, certo) l’idea della morte appare strettamente legata, sul piano linguistico, a quella del ‘coprire’ o ‘nascondere’, sottacqua o sottoterra – rimuovere dalla luce.

Note

[1] Per Nick Kent (1977), “eyes that seemed to burst out from his face, glazed with a kind of insect paranoia”; in un coevo articolo di Time (1977), “the demon-eyed New Yorker that could become the Mick Jagger of punk”. Lester Bangs (2018) trovava infatti da ridire sulla copertina di Blank Generation, dove Hell “riduce di proposito lo sguardo più penetrante e fanatico del rock al livello di un rospo drogato”.

[2] Batisti 2020.

[3] Ornaghi 2019.

[4] Merritt 2019.

[5] Giannakis 2019.